- Home

- Strait Fever Home Page

- Artist of the Decade

- Country Music Hall of Fame

- Dr. George Strait

- Special Achievemt. Award 2003

- Number Ones

- The Cowboy Rides Away

- Here For a Good Time

- Twang

- Troubadour

- It Just Comes Natural

- The Man

- What is it about George Strait

- Celebration: 30 Years

- King George Videos

- Stand There and Sing Lyrics

- CMAs 2007 & 2008

- Somewhere Down in Texas

- Seashores of Old Mexico

- Giants Alan Jackson

- Tx Stadium 2004 w/Alan & Jimmy

- Houston 2002 Astrodome

- Concert Photos

- Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame

- The Strait Story

- Albums

- Award Photos

- Award Shows

- Bubba Strait

- Jenifer's Foundation

- Honkytonkville

- Rehearsals CMAS 1999

- Strait Awesome

- GS Team Roping

- Straitfever 1999

- Straitfever 1994

- Wranglers

- Murder On Music Row

- Pure Country Memories

- Pure Country Photos

- Erv Woolsey

- Quotes & Interviews

- Ace In The Hole

- National Medal Of Arts

- Desperately, the Story

- D Label

- Copyright/Infor

- About Me

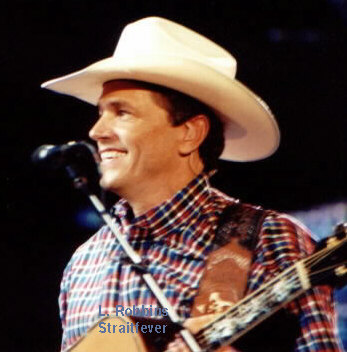

The saga of Murder on Music Row continues...

Click here to add your text.

"Murder On Music Row" Review

(Billboard, March 11, 2000):

If this isn't country music's dream team, what is? George Strait and Alan Jackson, two saviors of traditional country music in these pop-infused times, have joined forces to record a song that has tongues wagging. Penned by Larry Cordle and Larry Shell, the song was originally released on the current album by Larry Cordle and Lonesome Standard Time. It immediately created a ruckus on Music Row and stirred the passions of traditional country music fans. The well-written lyric charges that someone murdered traditional country music. Such lines as, "The almighty dollar and the lust for worldwide fame slowly killed tradition and for that someone should pay" are serving as a rallying cry for fans of traditional country music and generating tremendous listener response. The song is included on Strait's recently released "Latest Greatest Straitest

Hits" package, and though MCA has yet to issue the cut as a single, that hasn't stopped radio and listener from propelling the tune to No. 47 and Hot Shot Debut status on Billboard's Hot Country Singles & Tracks chart this issue. Musically, it's the kind of song that will make you reach for the nearest cold longneck beer. Lyrically, who can argue with the charges? And as for the performance, Strait and Jackson singing together is the ultimate musical treat for traditional country fans. This is more than a great record. It's a dead-on indictment of what's wrong with the country music industry today. It could just launch a revolution.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Excerpts From:

That killer country song

By Tom Roland, The Tennessean

published: March 15, 2000

Who's to blame for 'Murder on Music Row'? Songwriter Larry Cordle lays out the evidence.

Larry Cordle had no idea he would create such a furor when he literally wrote a killer

country song. Murder on Music Row. Your basic detective story in which death comes not to an individual but to an entire musical genre. Country music, the song proclaims, is history:

The steel guitars no longer cry And you can't hear fiddles play Drums and rock 'n' roll guitars are mixed up in your face

Cordle co-wrote the song with Larry Shell, adding it to his own bluegrass album, Murder on Music Row, last November as an afterthought. It gained attention on Carl P. Mayfield's radio show but has led to even more chatter since George Strait and Alan Jackson released a duet version on Strait's new album, Latest Greatest Straitest Hits.

It was, the songwriters say, a brave step for Strait and Jackson. After all, they record for major record companies, and record executives, among many others, are implicated as the culprits in the murder. "Don't you think it's because they (Strait and Jackson) can see?" Cordle asks rhetorically. "They're in the industry. It's going to be gone; it's slipping away."

In fact, numerous country records -- by Faith Hill, Shania Twain and Lonestar, for example -- have found their way into pop music in the last year. But, Cordle and Shell lament, those country-branded records are really pop records in disguise.

Those recordings have garnered huge sales. Thus, the labels, hoping to imitate those sales, are naturally looking for more music that imitates that sound. As a result, real, authentic country, with its drinkin' and cheatin' themes and painful instrumentation, may be encountering its own ice age. "I'm not against anybody making money," Shell says, becoming almost evangelical in his demeanor. "We all like to make money, and I would love to see them sell more records. But we cannot trample over tradition. We cannot do that. We cannot destroy what these people worked so hard for back in the 1940s and '50s to establish in this town."

Cordle and Shell have made a statement, event though that wasn't the original intent. Shell suggested the title, Murder on Music Row, during a conversation. The following day, they wrote it in a couple of hours..

Even during the Urban Cowboy period, there were a few banner-wavers for hard country, such as Gene Watson and Moe Bandy. Strait and Jackson, not so ironically, are the modern equivalent, although Cordle also counts Lee Ann Womack and Brad Paisley.

Cordle and Shell hope the current pop trend is just another part of the music's ongoing cycle. Despite the tone of Murder on Music Row, Cordle admits country music isn't quite dead yet. "I don't think it is," he says, with the caveat, "I think it's a heck of a lot closer to being (dead) than it ever has been." If country music does breathe its final breath, it's not just record labels and executives who should pay for the crime, Cordle and Shell insist. "I really think there's a lot of people to blame," Cordle says. "I think the record people are, I think the artists are, I think the creative people are."

It all comes down, he suggests, to Music Row's pursuit of the typical Nashville clone: pretty people singing positive, uptempo love songs, all suited for feel-good videos. "It's a pretty people's world," he assesses. "It's a TV world, and that bodes bad for music. Everybody ain't pretty that can sing and write and play."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Nashville Sound-Music Row

By JIM PATTERSON

Associated Press Writer

Nashville, TN. (AP)

August 24, 2000

The first time George Strait heard the song "Murder on Music Row," he wasn't supposed to take it seriously. MCA Records head Tony Brown played it for the star as an amusing curiosity.

Strait took it seriously. He recorded the song, which is about Nashville losing touch

with its musical roots, as a duet with Alan Jackson and put it on a hits album. It climbed the country charts to No. 38 with no promotion, or even an official release as a single.

Now, the country music industry, the very industry the song criticizes, has given "Murder on Music Row" two nominations for its prestigious Country Music Association Awards.

"It's the kind of tune that makes an impact," Brown said. "It was a cool event, and we had no idea that people would think it was industry-bashing."

But songwriters Larry Cordle and Larry Shell said their message was clear. Sitting in Shell's office a block from the skyscrapers of Music Row, the duo shouted with evangelical fever.

"We want our country music back, man!" Shell said. "There always comes a time in your life when you have to stand up for something or not be counted. We want to be counted that we are trying to stand up for country music with this song."

The pair believes such artists as Shania Twain, Faith Hill and Lonestar have threatened traditional country music with crossover hits that are pulling Nashville away from some of its musical and lyrical signposts.

Instead of divorce and drinking songs with steel guitars and fiddles, many Nashville

artists now strive to reach younger listeners with pop songs about first love.

From "Murder on Music Row": "The almighty dollar, and the lust for worldwide fame/Slowly killed tradition and for that someone should hang/Oh they all say not guilty but the evidence will show/That murder's been committed down on Music Row."

The version by Strait and Jackson is nominated by the CMA for best vocal collaboration, and Cordle and Shell are nominated for best song. The winners will be revealed Oct. 4 at the Grand Ole Opry House, broadcast live by CBS.

"It should be song of the year, there's no doubt about that," said Ricky Skaggs, a traditional artist who has abandoned mainstream country and gone back to bluegrass.

"I just think it's almost like a mirror that Nashville ought to hold up and look at itself. That is exactly what's happened."

Shell and Cordle credit the nominations to CMA's secret balloting process.

"No one knows you're voting for the song," Shell said. "So consequently, you can't be chastised for your vote."

The duo acknowledges that things aren't quite as dire as the song indicates.

Traditional artists Brad Paisley and Lee Ann Womack are having success, Jackson and Strait soldier on, and the Dixie Chicks have brought banjo back to mainstream country.

Shell came up with the title "Murder on Music Row" and took the idea to Cordle. They finished the song together.

"I thought it'd make a great album title," Cordle said.

So it became the title track of the latest bluegrass album by Cordle and Lonesome Standard, complete with album cover art showing a steel guitar being loaded into a hearse.

"The main thing (Nashville producers) want from songs today is `I love you and you love me 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year, and everything's wonderful all the time,'" Cordle said. "That just ain't life."

Shell said good country music digs much deeper.

"No matter how high-tech we get, people still are getting divorced somewhere today. Somebody just lost a loved one that they're grieving over. Somebody just lost his job down at the factory.

"Some ol' boys laid out drunk all night. And some ol' boy went out last night with another woman, not his wife.

"So the thing is, that hasn't changed, and it's not going to. It hasn't changed since the beginning of time. I can still write about it, and guess what? There's a guy or woman out there that can relate to it, if I write it right."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

0

9/28/2000

He Done It

His song dares to challenge the Nashville money machine. Somehow, though, songwriter Larry Cordle has gotten away with Murder.

By Marty Jones

Murder, he wrote: Larry Cordle has given new life -- and hope -- to the idea that Nashville should return to its roots.

Read about some other anti-Nashville songs.

Each year, the annual Country Music Association awards broadcast holds a few surprises, little drama and zero controversy. Unlike the Grammys or the Academy Awards, where viewers can expect at least a little bit of from-the-podium pontificating on current events or artistic issues, the CMA's are typically safe, self-congratulatory shmoozefests for the Wal-Mart crowd. This year, however, the marathon just might be worth tuning in to. Thanks to Larry Cordle's song, "Murder on Music Row," the 2000 CMA show (set to air Wednesday, October 4) will buzz with a tension that's rare in the land of shlock and faux graciousness. Because Cordle's tune -- a scathing swing at all that's wrong with mainstream country -- has been nominated for CMA Song of the Year. A cover of the song by George Strait and Alan Jackson has also been nominated for Vocal Event of the Year. Considering the song's message, this acclaim is about as unlikely as Ken Starr being invited to Hillary Clinton's Senate victory party.

The tune's elevation to CMA-nominee status -- a development fueled by Strait and Jackson's cover, a few gutsy DJs and countless listener requests -- has hammered a wedge between Music City's major labels and a portion of its audience. The song continues to gain ground months after its release, too. Cordle's full-length CD, Murder on Music Row, has been the top-selling bluegrass record in the country for months. Strait and Jackson's cover of "Murder" recently peaked at number 38 on the Billboard singles charts, making it the highest-charting country album cut in years -- despite MCA's (Strait's label) refusal to promote the song. According to Lon Helton, the country-music editor of trade magazine Radio & Record, the fact that two of country music's heavies are playing Cordle's number has stunned many. "Why would you go on TV," he says they've wondered, "and say, 'Hey, everybody, our product sucks'? There's a wide range of feelings around town about the song itself."

"This song has really created a stir," says Eddie Stubbs, one of the first Nashville DJs to play the song on his shows for WSM/650 AM, the host station for the Grand Ole Opry. "It puts into words what a lot of people around here have felt for a long time." One year since its release, Stubbs says the song remains his most requested tune of his evening show, one he plays every night. "It was an honor to play it when if first came out," says Stubbs, whose playing of "Murder" violated a station-issued mandate that he play no new music on his program, "and it's still an honor to play it. Because it makes a statement."

"Murder" does so in eloquent fashion. Over a stately, old-fashioned country tune highlighted by fiddle, dobro and his own honeyed drawl, Cordle expresses the ache of every fan who yearns for the emotion and reality of yesterday's country music. "Someone killed country music," he sings patiently, "cut out its heart and soul/They got away with murder down on music row." Unlike many of the songs that fit the Nash-bashing genre (see sidebar), Cordle's tune -- which he co-wrote with partner Larry Shell -- makes the point with care and concern instead of pissed-off venom. Not that he pulls any punches, however. "The almighty dollar and the lust for worldwide fame/Slowly killed tradition/And for that someone should hang," Cordle sings before pointing out that "the steel guitar no longer cries/And fiddles barely play/But drums and rock-and-roll guitars/Are mixed up in your face." Before the tune ends, Cordle delivers his ironic point: "Ol' Hank wouldn't have a chance on today's radio/Since they committed murder down on music row." The song is an astounding piece of succinct, heartfelt protest that connects on every level. If Song of the Year awards are doled out for genuine emotion, songsmithing craft and accurate reporting, "Murder" deserves the trophy.

According to Cordle, the tune almost didn't happen. Last summer Shell came up with the title, and the two men fleshed out the song in a few days. At the time, Cordle was in the last stages of recording his current platter (on Shellpoint Records) and decided to record the track after it received huge responses during a couple of his solo performances. When he debuted the song at Nashville's famed Bluebird Cafe, he recalls, "it was like a bomb went off in the place by the time I reached the hook. And those folks don't get excited about much there, because they've heard the best." When mixing his CD, Cordle still wasn't sure about placing the country tune on his bluegrass-flavored record. He eventually did. "I guessed that bluegrass fans would be traditional country fans," he says, "and I guessed correctly. But I had no idea it would strike such a big chord with so many people."

Why has it hit home for many country fans?

"People feel like Nashville has let them down and they have no voice," Cordle says. "Now they feel like we gave them a voice. And if I gotta speak for somebody, that's the folks I'd want to speak for, because I feel the same way. You know, selling a whole bunch of units is great. But I don't feel like you should try and totally wipe out a genre of music simply for bucks."

Cordle has made his share of bucks as a Nashville songwriter. Since arriving in Nashville about eight years ago, he's placed tunes with Trisha Yearwood, Loretta Lynn and Mr. Nashville himself, Garth Brooks, to name a few. He's also released his own recordings and, all told, estimates he's been on about 45 million pressed records. In his early-'90s Garth days, he says, he made "obscene" amounts of money and has been living off those royalties since then.

Along the way, he's come to face-to face with country's various killers. Cordle's list of Nash-villains includes Music City's money-minded corporate culture, full of business types with no appreciation for country music who defer to buck-passing when it comes to decisions on songs and style. Skyrocketing production costs are another enemy, he says, that amp up the need for hits and mean less risk-taking. Some artists are also at fault, in that they are too willing to dilute their craft and credibility (often under great pressure from labels) in pursuit of the million-selling home run. And for the songwriter looking to pitch songs these days, getting them before an artist is virtually impossible.

"Now," Cordle says, "you've got to play it for the A&R person, they gotta like it, they gotta play it for the label head, he's got to play it for the promotion department and the rest of the staff. Then they get the artist in to see if they like it." His own experiences with A&R men have been disturbing. "They're listening to my song reading a magazine," he says, his soft-spoken voice rising with disgust. "And then they fast-forward it before it gets to the end of the first chorus. At the end of that they tell you, 'Yeah, it's a great song. But it's too country.'"

"Murder," however, did reach Strait, through a manager who heard Cordle's version on the radio. According to Cordle and those familiar with the song's history, the executive allegedly played the song for Strait as a joke. The singer didn't find it funny and decided to record and add it to his Latest Greatest Straitest Hits collection at the last minute; Jackson soon signed on to join him on the cut.

Granted, for some country purists and alt-country fans, the "Crazy 'bout a Ford Truck" Jackson and the occasionally sappy Strait are not the proper team for prosecuting country's assassins. "It's insulting that these two men covered this song," says Mike Wall, whose Country Classics show airs on WFOS/FM 88.7 in Chesapeake, Virginia. "These men are the perpetrators of the very crime they're singing about. In espionage circles, they call this a double-cross." But Randy Harrell, president of Shellpoint Records (which released Cordle's CD) thinks the two were the very men for the job. "They're all we've got right now for mainstream country," he says. Cordle agrees. "It was stunning that they recorded it," he says. (Jackson does deserve points for his defiant, if abbreviated, rendering of George Jones's "Choices" at last year's CMA ceremony; the performance was a protest of the show's refusal to let Jones play the song himself in its entirety.)

The song's nomination to this year's CMA awards has once again put the debate over country music's content in the faces of Nashville's players and its audience. As usual, there are dissenting views. Some, like Lon Helton, feel the sentiments of "Murder" aren't shared by many in the country audience. He considers the song a "novelty" that doesn't reflect the majority of country listeners. "I see a lot of research," he says, "and the listeners are not clamoring for those old artists or that old sound. It all goes back to the question of 'What is country music?' And it's whatever country fans think it is. It grows and changes." Others, like Stubbs, see the song's popularity as an indication of fans' desire for change. When Strait came to Nashville recently, he saw ample proof of that argument.

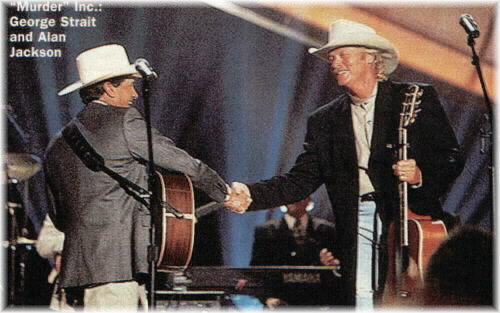

"Alan Jackson walked out on stage and sang ['Murder on Music Row'] with [Strait], and 54,000 people gave them a standing ovation. In Nashville. What does this tell you?"

Stubbs says the real beef for him and his peers is not whether pop country should exist, but why it does so to the exclusion of country's authentic forms. "This is not just about old music," he notes. "It's about substance, whether it's old or new. This song is about substance and the need for more of it. There should be room for it all -- that's what it's about." (Stubbs's revered roots-country show on WSM can be heard each weeknight at wsmonline.com. He also hosts a classic-country show each Saturday from noon to 3 p.m. Eastern time, at wamu.org.)

"It ain't Mutt Lang's fault," Cordle says, referring to Shania Twain's producer and husband, "that the format decided to play all these records that sound like Def Leppard. He could've competed in another arena; he just took the one open to him. Hey, man, he's smart to me. The problem I have with all those kinds of records is, why ain't they competing with Mariah Carey, Whitney Houston and Celine Dion? Because these are pop records, not country records. This town acts like they're embarrassed by what brought them to the dance. They respect their elders here by mouth, but they don't mean it. Hell, we got guys over here that can still tote the mail, that sold a lot of records, that still ain't in the Hall of Fame."

All of which doesn't bode well for "Murder" to win come October 4. "I can't imagine it winning," Cordle says, "but there again, I couldn't imagine it being nominated. Larry and I are both a little shocked. But whether it wins or not, we feel like we've won a victory of some sorts.

"I've been told," Cordle adds conspiratorially, "that MCA had a guy actively calling radio stations and asking them not to play the song."

Of course, the bigger victory Cordle's tune could achieve is to actually spark a change in the practices of Nashville's record execs. Cordle's not expecting that to happen, since it would require "admitting they're wrong. And this town is all about power. It's not about anything else, my friend."

Which means the joy of penning a tune that attempted to shift that power will be tempered by a dose of reality. "I talked to one of my old partners last week -- he's a session player in town," Cordle says. "I asked was he playing on some country records. He said, 'Cord, I'd like to tell you that I am. But the fact is, it's the same tune all day long -- it's just in a different key with a different singer.'

"My daughter is nine years old," he continues, "and she's been around all of this stuff. She sees these guys and girls on CMT and she says, 'Daddy, they're not country, are they?' And I tell her, 'No, not really.' And then she asks, 'Well why is it on CMT?' And all I can says is, 'That's a question I can't answer for you. You'll figure it out as you get older.'"

SHOWDOWN IN NASHVILLE:

George Strait and Alan Jackson shoot at the heart of the music industry

with 'Murder on Music Row'

By: Mario Tarradell

Date: May 11, 2000

The applause was polite but hesitant. As the camera panned through the star-studded audience it caught a glimpse of Reba McEntire, who sported a disdainful expression on her face. Clint Black, sitting not far from Ms. McEntire, pointed to himself and mouthed the words "Not me."

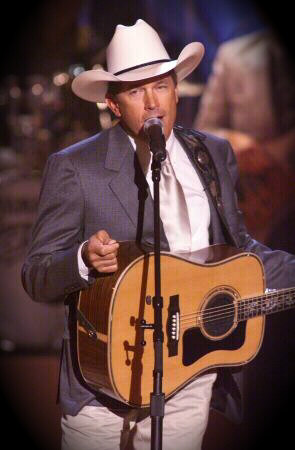

That was the scene at last week's Academy of Country Music awards after country superstars George Strait and Alan Jackson sang the controversial "Murder on Music Row."

The song, one of two new tracks on Mr. Strait's Latest Greatest Straitest Hits CD, has polarized the country music establishment. It's love it or hate it. Penned by Music City songwriters Larry Cordle and Larry Shell, the song is a biting, tongue-in-cheek slam against the industry for marketing pop-sounding country singers while die-hard artists struggle for a breakthrough hit.

The tune's second verse says it all: "The almighty dollar, and the lust for worldwide fame slowly killed tradition and for that someone should hang/Oh they all say not guilty but the evidence will show that murder was committed down on music row."

Fighting words, especially for an industry still reeling from the fallout of the "90s country boom. Record sales have leveled off, and today a radio hit doesn't guarantee a top-selling album. Plus, such a pointed song can't be ignored when it's sung by two country titans.

"I thought they were nervous but I thought they did the song real good justice," says Mr. Cordle about the Strait-Jackson ACM performance.

"They're standing there trying to do this song, looking at all the people they were singing about sitting right in front of them. But I thought they did good, they were trying to say something. And I am absolutely happy with the recorded version of the song. I couldn't have asked for a better record or two better guys to do it."

But even with the phenomenal star power and more than 14 million ACM viewers as a test audience, MCA Nashville has no plans to release "Murder on Music Row" as an official single.

"It was once under consideration," says David Haley, MCA Nashville's vice president of national promotion. "But there were several things that had to be considered. There's also the performance on the ACMs and we were waiting for a gauge from radio. And we found out that fan response was not overwhelming, regarding phone calls and e-mails into the radio stations." Still, 50 out of 156 country stations nationwide are playing the song. "Murder" managed to reach No. 38 on Billboard's country singles chart in late April, making it the highest-charting nonseasonal album cut ever. For some of the programmers currently spinning the song, the controversy is not an issue.

"It's George Strait, it's Alan Jackson," says Linda O'Brian, music director for Arlington's KSCS-FM (96.3). "When was the last time you had two heavy hitters in country music working the same project? We're talking about the big heavy hitters of our format. We're talking about the Emmitt Smith and the Troy Aikman of our format. People, get with the program. This is a no-brainer."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

12/22/2000

Excerpts: East Bay Express, Online

Nashville Suits

When Garth Brooks' first two albums sold over ten million copies each, it sent the Nashville greed machine into overdrive.

By J. Poet

When one considers the panoply of mind-numbing and soul-chilling problems facing humankind in the early days of the new century, the uphill battle facing lovers of alt-country music hardly seems worth mentioning. Still, Nashville's resistance to this back-to-the-roots movement, as characterized by the flap around "Murder on Music Row," a song by Larry Cordle and Lonesome Standard Time, draws certain disturbing parallels to this year's election fiasco.

Cordle's song was the number-one choice of fans responding to radio-stations and magazines for Best Song of the Year pollsyet several editors and program directors "disallowed" the song, claiming that nobody really wants to hear this kind of country music anymore.

The most disturbing thing in both casespicking a President and a number-one songis the disregard of the public's will. Voting irregularities in Florida point out the fallibility of the system; but rather than admit it and try to fix it, the candidates, their lawyers, and the judges have ignored the voters' will in an effort to skew the results. The major labels in Nashville, which the lyrics of "Murder on Music Row" lampoon, have likewise done everything in their power to bury the song, ignoring the will of the record-buyers, who vote with their dollars and with their responses to polls.

In the mid-'70s, country started getting slick. Billy Sherrill, who produced bedrock hits like "D-I-V-O-R-C-E" for Tammy Wynette, started adding strings and background vocals to sessions, and looking for pop hits they could "countrify." Many producers followed in his footsteps. I hated "countrypolitan," as it was called, and started buying back-catalogue stuff by Stonewall Jackson, Jim & Jesse, Buck Owens, and other honky-tonk heroes who made music with a little backbone. Things brightened up in the '80s with Randy Travis, the Judds, Clint Black, Joe Barnhill, and other "hat acts." They dropped most of the pop influences and went back to good lyrics and solid musicianship that balanced the growl of electric guitars with bluegrass-influenced mandolin pickin' and fiddle playin'. Then along came Garth Brooks.

To be fair, Brooks always balances his rock-influenced power ballads with solid honky-tonk rockers, but when his first two albumsNo Fences and Ropin' the Windsold over ten million copies each, it set the Nashville greed machine into overdrive. After seeing that kind of money, no record label was going to be satisfied with a Randy Travis selling a mere 500,000 albums. Country became Big Business, and only pop music would keep the cash flow high.

When "Mutt" Lange, famous for sending Def Leppard and AC/DC into heavy-metal heaven, started producing and later married "country" singer Shania Twain, country music at least the country music I had always lovedwent into the tank. Songs about hard times, hard luck, and hard drinkin' went out the window. As alt- country singer Tom Russell remarked: "Today's country music ain't nothing but Aerosmith with a southern accent."

For most of the '90s, people who wanted to listen to hard-core country music had to forget about the artists on major labels (with rare exceptions like BR5-49, Junior Brown, or Lyle Lovett) and look for upstarts like Russell, Deke Dickerson, Robbie Fulks, Dallas Wayne, Bad Livers, Robin and Linda Williams, Freakwater, and all those hundreds of others now categorized as alt-country, twangcore, Americana, or No Depression. (The bimonthly No Depression magazine is the current bible of the alt-country movement.) But as everyone who follows the music business knows, all things are cyclic, and most felt that it was only a matter of time before the pendulum would swing back and usher in another era of "real" country music. Unfortunately, the "Murder on Music Row" saga seems to indicate that even if the pendulum does swing back, the suits that run (or is that ruin?) today's country music business will ignore it.

I first heard about "Murder on Music Row" from Hazel Dickens, one of the best hard-core country and bluegrass singers working today. When I interviewed her for Pulse magazine last January, she made the expected complaints about Nashville, and then told me she'd recently heard a tune called "Murder on Music Row" that summed up her feelings.

"It's about the death of roots country," Dickens said, "and when the DJ played it, he said the phones lit up like he'd never seen."

In case you're thinking Cordle is crying sour grapes, he's not hurting for money or recognition. A few of his tunes were on Garth Brooks' first two albums, which made him a huge amount of money. Shell runs a music publishing company, and, like Cordle, is no stranger to success. But both men had been feeling that "real" country music, addressing the real situations of real people, are few and far between.

Most country music stations today don't play country music, and even on their oldies shows, you seldom hear a track by Merle Haggard or George Jones. This particular bit of hypocrisy reached its apex at last year's Country Music Association awards show. George Jones was nominated for his song "Changes," but the CMA told him he could only sing one verse on its awards show. The CMA said the show was running too long, but the conspiracy-minded suspected that the tune was "too country" for the "new" CMA. Jones prevented an on-air controversy by refusing to play at all, but when Alan Jackson, a star who always includes a few hard-core tunes on his albums, got up to sing, he added a chorus of "Changes" to his own number.

Tony Brown, head of MCA's Nashville division, called Cordle and said he wanted to play "Murder on Music Row" for George Strait so Cordle sent his office a copy, and Strait recorded it as a duet with Alan Jackson for his Latest Greatest Straitest Hits CD. "Murder on Music Row" took off, reaching #38 on the country singles chart, based on radio airplay, despite the fact that MCA never released the song as a single. Arista, Jackson's label, also failed (or refused?) to release it as a single, and both labels did nothing to promote the song in any way. MCA, in fact, was actively calling country stations and asking them not to play the song.

When the time came to compile the votes for the year's "best of" lists, many radio stations and magazines found "Murder on Music Row" topping the charts in the Best Song category. Some stations and magazines dismissed the results of the polls, but then the tables turned again.

Anyone for a ballot recount?

The notoriously conservative CMA nominated "Murder on Music Row" for Song of the Year, Vocal Duet of the Year, and Vocal Event of the Year. "To say I was surprised would be an understatement," Cordle told me, "but I'm glad the balloting is secret, so no one knows [who] voted for the song. Consequently, you can't be chastised for your vote."

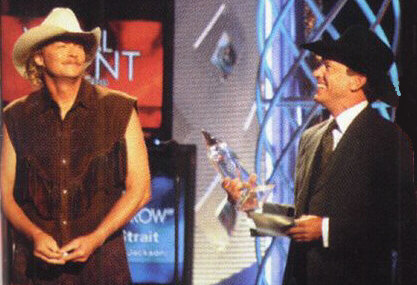

When the CMA awards show aired, it featured Strait and Jackson belting out "Murder on Music Row"and although it didn't win Song of the Year, the tune did take home the Vocal Event of the Year award.

One small step for a songwriter, but whether it will lead to one giant leap for "real country music" remains an open question. Is it really that scary to hear what people think?

Recording "Murder On Music Row" didn't hurt the careers of Alan And George, not where the fans are concerned... and they're the ones that matter!

Wednesday June 13, 2001

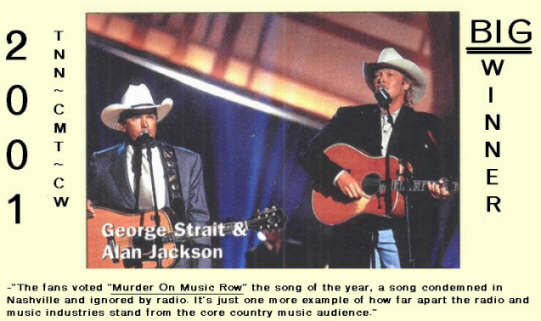

Strait, Jackson Win Big at TNN Awards

By JIM PATTERSON, Associated Press Writer

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) - An absent George Strait was named the top entertainer in country music on Wednesday and shared three fan-voted awards with Alan Jackson for their duet ``Murder on Music Row.''

Strait and Jackson won best single, song and collaborative event for ``Murder on Music Row'' at the TNN & CMT Country Weekly Music Awards. The song decries the lack of support of older country music styles

``This song probably rubbed a few people wrong, but I'm glad there's still a lot of people out there that still like what it says,'' Jackson said. ``I don't mean everything on country radio has to sound like Hank Williams, but maybe some now and then.''

Strait also won the Impact Award, for expanding the influence of country music in other mediums. He has done a series of commercials for Chevrolet trucks.

Jackson was the top award winner, winning six of the eight categories in which he was nominated. He was named best male vocalist, and won best album for ``When Somebody Loves You'' and best video for ``www.memory.''

``It's been a pretty good night so far,'' Jackson said. ``I wish George (Strait) was here to say something.''

That comment was met with laughter from the audience. Mr. Strait and Mr. Jackson had just completed the George Strait Country Music Festival Tour for 2001 only days before.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Thursday June 14 2:08 AM, 2001

Alan Jackson sweeps music awards in Nashville

By Pat Harris

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (Reuters) - Fans overwhelmingly endorsed traditional-style country music on Wednesday by voting a clean sweep for Alan Jackson with a total of six trophies at the TNN & CMT Country Weekly Music Awards Show.

Runner-up was George Strait, also a traditionalist, who won five prizes.

Three of their awards were for ``Murder on Music Row,'' a song the two sang as a duo accusing Nashville's country music industry of increasingly trending toward pop.

The song won the song-of-the-year prize for them along with songwriters Larry Cordle and Larry Shell, plus awards for collaborative event of the year and single of the year.

Strait also won the coveted entertainer of the year prize and the Impact Award for contribution to country music in motion pictures and TV commercials, while Jackson won male artist of the year and CMT music video of the year for ''www.memory'' plus ``album of the year for ``When Somebody Loves You.''

The show was televised over cable channels TNN and CMT from the Gaylord Entertainment Center in downtown Nashville, kicking off the city's four-day Fan Fair 2001.

Another top artist, 44-year-old Vince Gill, who won the career achievement award, told reporters back stage, ``I've always said that country music can do all those new things so long as it keeps its core, but that ... core seems to have disappeared and the fans are saying that, too.''

Strait was unable to attend the show, but his award was accepted for him by Jackson, who said he was not surprised that ''Murder on Music Row'' struck a chord with fans.

The lanky singer, whose career began in 1985, told reporters, ``I think there's still a market for country music out there and a lot of the fans really care about it.''

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Case Still Not Closed On 'Murder'

By Wade Jessen 615-321-4291 wjessen@airplaymonitor.com

June 29, 2001

CONGRATULATIONS, WE THINK: The fans spoke at the annual TNN & CMT Country Weekly Awards, a June 13 simulcast on the cable outlets, where George Strait, Alan Jackson, and their duet, "Murder on Music Row," were the most awarded of the evening. But the celebrated song did not have a noteworthy increase in spins at our monitored stations after winning the show's triple crownsingle of the year, song of the year, and best collaborative event. Not surprisingly, given the resistance to the song at its release, in the seven days following the show, "Murder" increased just one spin over the same period a week earlier.

Only 18 of our 152 monitored stations played the song between June 14 and June 20, resulting in 25 total detections for the period. Two weeks prior to the awards show, only 19 spins were tracked.

Though it's inaccurate to say that the entire country radio universe shunned the song as a current, the airplay that pushed it to peak at No. 38 last spring was largely because of the event nature of the duet, to which its message took a back seat as a necessary evil. At its peak performance on our Country Airplay chart, roughly half of our radio panel contributed to the airplay total.

And unlike most other records, there was little chest-beating in the format about who played "Murder" first or who played it most. That credit is shared by WSM-AM Nashville evening personality/Grand Ole Opry announcer Eddie Stubbs and WKDF (Music City 103) Nashville morning man Carl P. Mayfield, who each made Larry Cordle & Lonesome Standard Time's original take a staple on their respective shows long before the duet version was recorded.

It's also an interesting argument in the song's favor that it took the TNN/CMT Award for single of the year, when it was never released as a single. Apparently, the will of the fans upstaged the awards criteria in the single category.

The duet version of "Murder" is available only on Strait's platinum Latest Greatest Straitest Hits (MCA Nashville). In the four full shopping days after the awards show, Strait's album improved enough to take the Billboard Top Country Albums chart's Pacesetter designation (a percentage-based highlight for the biggest increase on the chart) with an 83% gain. His current self-titled release gained 30%, which suggests that although he was a multiple winner at the show (including entertainer of the year), Strait's hits package was helped significantly by the impressions made with the "Murder" accolades.

For many PDs, the "Murder" story ended when the song ran its course as a current and they no longer had to deal with it. Those programmers will remember the song as a controversial novelty and not as a courageous editorial on the state of country at the beginning of the new century. But look at the discourse that's taken place over the past year or so, from broadcasters to label presidents, and it's clear that at least some industryites got the message whether they owned up to it publicly or not.

Nobody saw him running from 16th Avenue

They never found a fingerprint or the weapon that was used

But someone killed Country Music, cut out it's heart and soul

They got away with murder down on Music Row

Click here to add your text.

The almighty dollar, and the lust for worldwide fame

Slowly killed tradition and for that someone should hang

Oh and they all say not guilty but the evidence will show

That murder's been committed down on music row.

Old Hank wouldn't have had a chance on today's radio

Since they've committed murder down on music row.

They thought no one would miss it once it was dead and gone

They said no one would buy them 'ol drinkin' an cheatin' songs

Well there ain't no justice in it and the hard facts are cold

Murder's been committed down on music row.

CHORUS:

For the steel guitars no longer cry and fiddles barely play

with drums and rock and roll guitars mixed right up in your face

The Hag he doesn't have a chance on today's radio

Since they committed murder down on music row.

Why they even told the possum to pack up and go home

There's been an awful murder down on music row.

After they performed "Murder" at the Academy of Country Music Awards

Congratulations George and Alan for winning Vocal Event of the Year

At the October 4th 2000 Country Music Awards

In this case... "crime" did pay.

The continuing saga.. .

Click on the link below for

concert photos

of George and Alan performing "Murder On Music Row" during the 2001 George Strait Country Music Festival Tour

I'm always looking for more photos for this site so if you have some to share let me know, my email link is below.

My deepest thanks to all of my Strait-fevered friends who contributed to this page!

George Strait

and

Alan Jackson

So continues the "never ending" story. Strait co-producer and MCA "cool cat" Tony Brown heard this song and brought it to George, somewhat as a joke. George knew it was a good song, though perhaps a bit controversial. Although he knew he was taking a chance by recording it he made up his mind to do so. He called Alan Jackson and asked him to join him in the studio, and Alan being the Country Man he is was only too happy to oblidge. The result is a great recording of a great song that was never released as a single. Record companies didn't hear the cry of the fans of Country Music but instead listened to what radio programmers decided to tell them. The influx of pop into Country had steadily decreased the play of true Country Music on stations, and programmers went with what "New Country/Cross-over pop" fans wanted to hear.

This song reached number 38 On Billboard due to persistant requests from Country Music Fans like myself to stations that are Country, listened to the fans, and played the song. Hellllooo Radio, and wake up Nashville!

Those "New Country" radio people don't know what Country Music is all about. Some stations outright refused to play the song, no matter how much fans requested it . To my mind that's a clear statement that the truth in the lyrics hurt the guilty parties. The "almighty dollar" in "pop flavored New Country" music is more important to the industry then preserving the integrity and the sound of honest traditional Country Music.

Meanwhile, back in the back of our memories Country fans know what they want, and it ain't rock or pop. We tune in to Country stations to hear C-O-U-N-T-R-Y Music, and while "change" can be good, and music can appeal -- if it's a good song with strong melody and good lyrics -- the roots must remain true. There is no need for an artist to put forth a public effort to be sexy and different, not if they have genuine talent, and are concerned about the heart of their craft. Get off the fence folks, if you want to sing pop go do it, and leave Country Music alone. If the song doesn't talk about the ups and downs of life, the living, losing, and loving, if the voice isn't feeling the music and telling the story, and you can't hear that steel guitar, and those twin fiddles it just ain't Country -- I'm not listening to it, and I'm not buying it.

Music has always been a big part of my life, I love all generes of music, and while I can and do appreciate a well-written song sung with talent, style, and heart I love honest traditional Country Music the most. When I turn on my Country Station I want to hear Country Music.

If you wish to contribute to this tribute Page send your comments to me, Straitfever@aol.com

~ Linda Robbins

"Murder On Music Row" is COUNTRY music at it's finest. You can find this single on the "Latest Greatest Straitest Hits" by George Strait. Here you have two of the best voices in COUNTRY music collaborating on a great song to make a powerful statement.

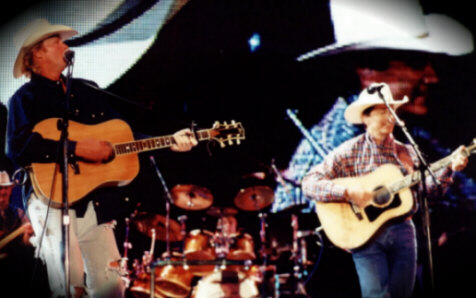

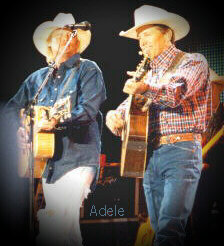

On April 30th, 2000 the George Strait Country Music Festival made it's presence known in Nashville, Tennessee. George Strait took the stage as darkness fell on the Adelphia Coliseum. During his show a special moment arrived. Fans exploded with anticipation as Alan Jackson strolled on stage to join Mr. Strait in performing "Murder On Music Row."

It was the first time they had sung "Murder On Music Row" for Country Music fans, over 54,000 of them. I was in second row center and it was a special moment during an unforgettable show. Following are photos from that show along with the song lyrics.

November 7th 2001

CMA Song of the Year -

"Murder On Music Row."

Country Music Magazine, April/May 2002

Excerpt regarding "Murder On Music Row" from a wonderful interview with George Strait;

James Hunter

: "You've never been the center of controversy -- at least not until "Murder On Music Row," your duet with Alan Jackson that criticized the pop influence in country. What did you think of the song when you first heard it?"

George Strait:

"I died laughing. I never dreamed that it would be so controversial in the country music business. It says what it says,. But I just thought "Well, it just pokes fun at Nashville." It's not an in-your-face slap at the industry, I didn't think. It's just a discussion that I've heard since "81 when I signed with MCA and we're still hearing today. I love traditional country music, and I love to sing it, and I think it will always be here. I'm not worried about it at all."

This page was last updated on: December 4,

2002

Wednesday June 13, 2001

Winners of the TNN & CMT Country Weekly Music Awards included our heroes:

Entertainer: George Strait.

Male artist: Alan Jackson

Impact Award: George Strait.

Collaborative Event: ``

Murder on Music Row

,'' Alan Jackson & George Strait

Album: ``When Somebody Loves You,'' Alan Jackson

Single: ``

Murder on Music Row

,'' Alan Jackson and George Strait

Video: ``www.memory,'' Alan Jackson

Song: ``

Murder on Music Row

,'' Alan Jackson and George Strait

(songwriters Larry Cordle, Larry Shell)

*

George and Alan's duet of "Murder On Music Row" was nominated for a Grammy Award in 2001 as Best Country Collaboration With Vocals.

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

">

CHORUS:

For the steel guitar no longer cries and fiddles barely play

But drums and rock and roll guitar are mixed up in your face

Lyrics and Concert Photos

">

">

">

">

Cl

* Proof that a good song can stand on it's own.

MURDER ON MUSIC ROW

Limousine Cowboy

With 50 million albums sold, George Strait really doesn't need to bother with the business side of country music

By JIM PATTERSON

Associated Press

Tuesday, November 6, 2001 Page R3

NASHVILLE -- George Strait's new album, The Road Less Traveled, is being released today, just a week before the highly anticipated comeback album by Garth Brooks. Concerned about the competition, George? Strait laughs. "This is news to me, right now," he says of the heavily publicized Nov. 13 release of Scarecrow, Brooks's new album. "I didn't even know that."

Strait, 49, a bit more grey and much more talkative than his public persona, doesn't keep up with the business side of country music. "Why should I?" he says. Then he laughs -- for a long time. Strait's albums -- he releases one each year -- spawn hits and sell well. He's done a tour of stadiums for four years. It added up to 16 days of work this year. The rest of the time? "I rope," says the native Texan. "I stay at my ranch a lot. I love to deep-sea fish, and we do that a lot." He does pay attention to the music. He believes his new album is his best in years, though he's not sure why things came together so well. "I always have the intention of making a better album when I go in," he said. "It just doesn't always work out that way. I'm sure that every artist feels that way."

The Road Less Traveled is indeed a return to form for Strait, who's sold more than 50-million albums and scored such enduring hits as Amarillo by Morning. The first hit single, Run, is an effective change of pace; a moody, reflective song from a singer known for straight-ahead country. My Life's Been Grand, a Merle Haggard song, is an elegiac nod worthy of Frank Sinatra, one of Strait's idols. But the real shocker on first listen is Rodney Crowell's Stars on the Water. Effects have been added to Strait's voice to give it a robotic feel, like Cher's on the dance hit Believe. This from the guy who complained with duet partner Alan Jackson on the hit Murder on Music Row that traditional country music was losing out to pop sounds. He laughs even longer this time. "Really, my producer Tony Brown did that," Strait said. "I really didn't care for it at first. . . He kept easing it off and easing it off. I kind of like it now." Strait's never been the musical purist that Murder on Music Row suggests. He appreciates great singers and doesn't adhere to a particular style or genre. He loves the work of Sinatra as much as he does that of Haggard. "When I listened to Murder on Music Row the first time, I laughed," Strait said. "I thought it was funny because people are always worried about the traditional country music, which happens to be my personal favourite. "I certainly didn't mean it as a slap in the face. It was just poking fun at the people that were having the same conversations [about country music] for 20 years."

In The Real Thing by Chip Taylor, Strait criticizes music that strives too hard for crossover appeal. Early rock 'n' roll acts Pat Boone and the Crew Cuts (Sh-boom) are singled out. "I don't want you under my roof/ With your 86 proof/ watered down till it tastes like tea/ If you're gonna pull my string/ Make it the real thing for me," Strait sings. Again, he anticipates some fans will take the words too literally. "It's just a fun song," he said. "I like some of the lines in it, you know? They kind of ring true."

Strait was heralded as the great hope of traditional country in the early 1980s when he became a star. He was signed to MCA in 1981. Unwound that year started a streak of hits that continues to this day. Though Brooks is credited with influencing a generation of country singers in cowboy hats, print shirts and jeans, it's often overlooked that Strait was Brooks's early model. Strait says he doesn't spend time worrying about who gets credit for what.

"I'm just going along and enjoying every minute of it, hoping that it keeps on," he said. "It's going to be over someday. And when it is, I'm not going to like it, but I'm going to accept it. I've had a good career. But I'm going to ride it as long as I can." Then he lets out that satisfied laugh again.

MURDER ON MUSIC ROW